Upland farmers who relied on government promises to adequately pay them for improving the natural environment and tackling climate change have been short changed. Many are now living on less than the minimum wage due to inadequate scheme development and reward. So says new modelling carried by the University of Cumbria’s Prof Julia Aglionby. Work underway by AHDB confirms the scale of financial challenges for this unique group of England’s farmers.

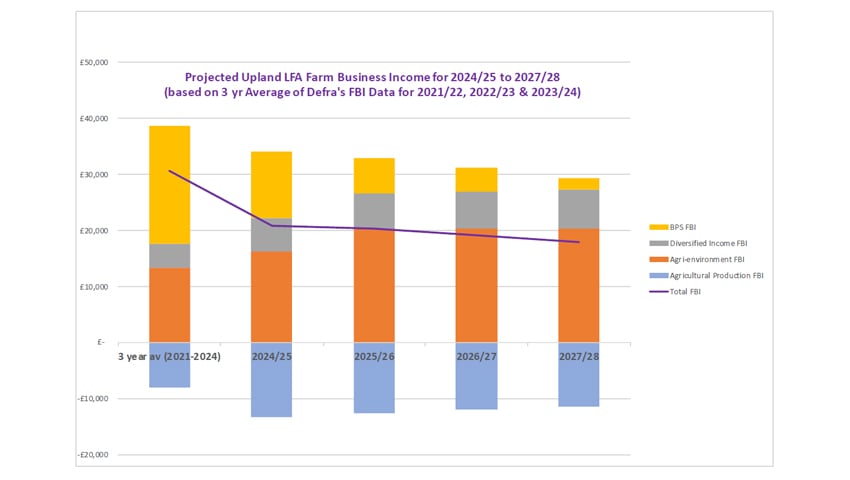

The modelling shows farm incomes set to decline by over a third over next three years, taking the average hill farm income well below the living wage. This will only make it harder for farmers to deliver the government’s environmental targets.

Professor Aglionby told 8point9 news, “It’s quite depressing, if we’re looking forward, as to what the future is going to hold for upland farmers, we’re seeing that farm business incomes are going to decline. My modelling is looking at the cost centres that Defra used – so I’ve used exactly the same approach that Defra used to find business income and tried to predict for the next three years. What we are showing is that the income for farms is going to decline and this is because the basic payment scheme is going down, but we’re finding that ELM isn’t replacing that. There isn’t the ability for people to transition – and in particular the majority of upland farms are stuck in old legacy schemes, both high-level stewardship and also the old countryside stewardship schemes.

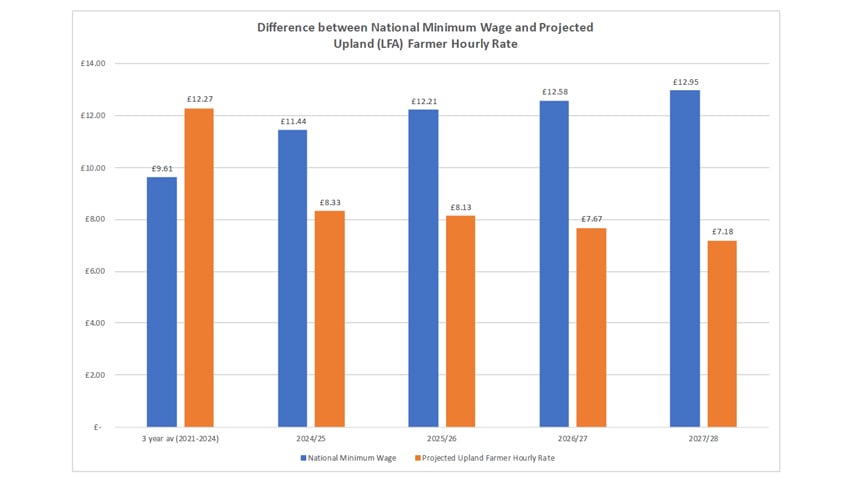

“There’s a moral case here. Can we expect people to work and deliver if they’re receiving only 55 per cent of the minimum wage? Many people don’t understand that a farm business; the profit, is what you use to pay yourself. It’s the same as a plumber – they are self-employed businesses. The data is showing that by 2027/28 we expect the farm income to equate to about £7 an hour – that’s really not acceptable and we can’t expect people to do a good job at that level.”

Although at a record high, current prices for beef and lamb, the main products of upland farming, do not provide a sufficient income to fund the costs of farming in a manner that delivers for nature, water, the climate, recreation and all the other public benefits we expect from the uplands. The modelling makes clear that upland farmers are heavily dependent on the Government funding, but to date the offer and opportunity has fallen well short of what is required.

The priority must be to recognise the impact of the end of the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS), on which many if not most upland farmers depend. Payments under the scheme are set to be completely phased out by 2028, with a significant reduction in 2025.

Christopher Price, Chair of the Uplands Alliance and CEO of the Rare Breeds Survival Trust, said, “The English uplands form some of our most iconic landscapes, providing wonderful habitats for a variety of species, helping to deliver on climate targets and supporting sustainable farming practices. They should be a core concern of any government concerned about the future of farming and the environment.

“Sadly, as the modelling shows, this has not been the case. Government schemes intended to support environmental land management in the uplands are not capable of meeting the scale of the challenges and have not been backed up with anything like sufficient investment. Government needs to reflect on the full range of benefits our uplands provide, and work with the full range of stakeholders on how they can be best maximised and delivered.”

The new Environmental Land Management (ELM) schemes are intended to help farmers meet the cost of addressing environmental challenges, and over time the modelling shows it will provide some significant additional income. The recently announced moorland payment rates are attractive.

However, the new ELM scheme is still far from being a complete solution.

In particular, the majority of upland farmers are stuck in Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) schemes available under the old farm support system and so are not eligible to participate in ELM. HLS payment rates have not increased for 20 years. This was not too much of an issue when BPS was available to underpin the HLS payment, but it is now.

If participation in the new ELM scheme is available, it is not cost free. Many of the options require farmers to spend time and money on the delivery of environmental benefits to secure the payments

On top of all this, Government IT systems are not yet able to offer new agreements for common land which makes up 40% of England’s Moorland.

The modelling shows farmers are exploring diversified, non-farming income streams, which are expected to yield a slight increase in overall income. However, there are clear limitations on the range of alternative employment opportunities available to upland farmers, and this option often isn’t available to tenants.

Over the years, particularly since Brexit, a number of farming and environmental organisations have come together through the Uplands Alliance to propose ways to support the range of benefits delivered by our uplands, and we hope that 2025, with a new government in charge, presents the opportunity to urgently drive this agenda forward.

Professor Janet Dwyer OBE, Professor of Rural Policy, Countryside and Community Research Institute, at the University of Gloucestershire, said, “As someone who works closely with farm businesses across Dartmoor and Exmoor, I have seen at first hand the shocking financial impact of government policy changes on the incomes and prospects of families who are dedicated to managing these upland environments for the benefit of present and future generations.

“The agricultural transition has created a significant shortfall in market and policy support which has not been seen since the last war, when government first recognised the importance of targeted support to keep the hills alive and to protect these amazing cultural landscapes and their unique ecosystems.

“Cutting these farms’ BPS payments whilst failing to offer them access to new schemes that should replace this funding and help them to invest in sustainable systems for the future, would mean government is turning its back on efficient and dedicated farming families who have devoted huge time and effort to delivering what agencies have asked them for, under previous environmental schemes. This seems a completely unjustified betrayal of trust and can only lead to negative outcomes for nature and for the millions of people who visit and enjoy these places, every year.”