A TEAM of Australian and Dutch scientists have written in PNAS Letters. They say that “Restoration of coastal marine habitats – often conducted under the umbrella of “nature-based solutions” – is one of the key actions underpinning global intergovernmental agreements, including the Paris Agreement and the 2021–2030 United Nations (UN) Decade of Restoration.

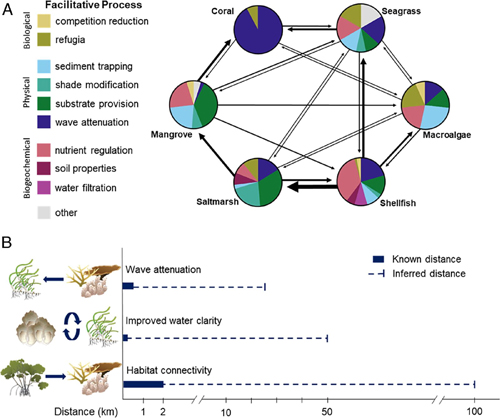

“To achieve global biodiversity and restoration targets we need methods that accelerate and scale up restoration activities in size and impact. Part of the solution is cross-habitat facilitation – positive interactions that occur when processes generated in one habitat benefit another. These interactions involve physical, biological, and biogeochemical processes, such as wave energy dampening, competition reduction, and nutrient cycling.”

Coastal habitats can be highly productive and diverse, supporting livelihoods and biodiversity.

“Facilitative, or positive, cross-habitat interactions, such as wave breaking by coral reefs or sediment trapping by seagrass and mangroves, enable other habitats to persist and thrive. And yet, restoration activities are not usually planned across multiple habitat types.

“To date, positive cross-habitat interactions, known as ‘facilitative interactions,’ underpin coastal ecosystem development, resilience, and expansion, but have received little attention in coastal marine restoration practice beyond small-scale studies.

“We found that only 6 of 2,145 coastal marine restoration studies addressed restoration of multiple habitats concurrently, and just 6 explicitly aimed to harness cross-habitat facilitation. In contrast, terrestrial ecosystem restoration often employs multihabitat restoration approaches.

“And yet,” say the scientists, “these interactions are incredibly important for habitat formation. Without cross-habitat facilitation via oyster and coral reefs that baffle waves, for example, saltmarshes, seagrasses, and mangroves cannot naturally develop in many locations.

“Biotic interactions, such as species migrations, can mediate long-distance cross-habitat facilitation. Cross-habitat facilitation can extend beyond coastal marine seascape interactions to interactions across marine–terrestrial borders. For example, nutrient exchange between land and sea can increase sand dune or reef productivity.

The scientists argue that successful scaling of coastal marine restoration requires a conceptual and practice-based shift from single-habitat practices to restoration endeavors that focus on rebuilding multiple, connected habitats across seascapes.

They say that “Physical, chemical, and biological connections among coastal marine habitats determine how they are characteristically distributed in seascapes. For instance, seagrass and mangroves are found in quiescent waters, which in the tropics are often formed by offshore coral reefs that act as a “wave break”. In turn, seagrass and coral reefs are often located offshore of mangroves, which trap sediments to create water clear enough to support photosynthesis. These close connections among habitats mean that the loss or degradation of one habitat type can have negative outcomes on adjacent ecosystems. To promote resilience and sustainability, restoration designs should consider how the spatial configurations and dependencies of multiple habitat types affect one another in positive ways.”

They say “A variety of barriers can hinder the adoption of multihabitat restoration. They include insufficient understanding of how multiple restored habitat types interact over different temporal and spatial scales, stakeholder conflicts, inadequate funding to achieve multihabitat restoration, a lack of cross-discipline perspectives when planning and designing restoration, and permits that do not consider multiple habitat types and may ultimately prevent incorporation of multiple habitat types in restoration designs.

“Furthermore, the current paradigm in restoration practice among permitting bodies and practitioners seeks to minimize negative interactions, such as competition, rather than harness positive interactions. Although most restoration is done on single habitats, at the seascape scale, this may result in intentionally spacing restored habitats away from other habitats to reduce the chance that restoration of one habitat might negatively impact adjacent habitats.

“Although interactions among different habitat types are not universally positive, we can avoid negative interactions in multihabitat restoration practice by identifying the distances between habitats where facilitative interactions are most common and use these to design the spacing and configuration of restoration.”