NEW RESEARCH by an international team of scientists investigates the role of meat in the human diet in terms of evolution and nutrition.

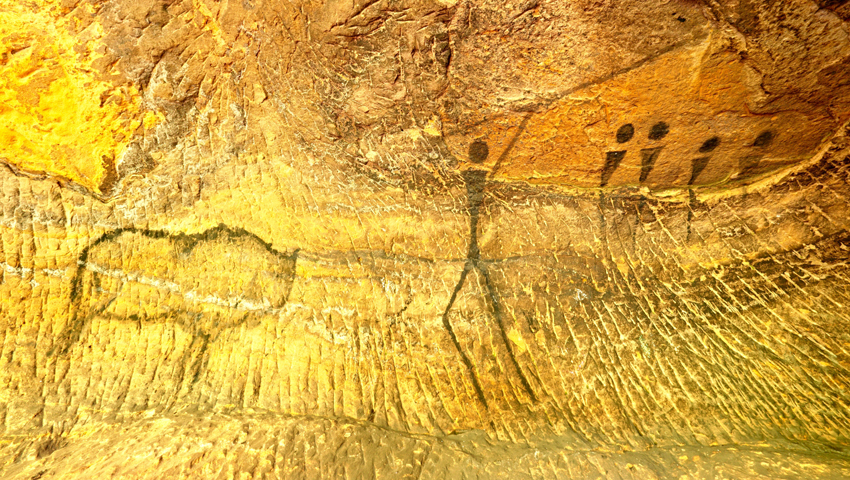

They say that historically and from an evolutionary perspective, meat has been cherished by human communities as a nutritious and highly symbolic food, against a 3-million-year background of biosocial needs. Whenever intake was low, this was mostly due to limited access and availability or because of ideological and religious reasons. Today, however, arguments for a widespread reduction of meat consumption have emerged from various actors, mostly in high-income countries.

Leaving aside the degree of negative impact that meat may have on a variety of factors that relate to human and planetary health, the purpose of their article was to summarize the positive nutritional aspects of meat consumption. Four key questions were identified.

First, to what degree can meat be considered as a part of the species-adapted diet of humans, and therefore as an appropriate food from a physiological and nutritional perspective? Second, what are the key nutrients that meat provides and could potentially become challenging to obtain from other sources in meat-free diets? Third, what is the current contribution of meat to the global supply of such nutrients and how does that differ regionally? Finally, what would be the implications of a substantial reduction in meat consumption on human nutrition and well-being at large, especially for populations with increased needs and in regions where intake is already worryingly low?

The researchers found that aspects of human anatomy, digestion, and metabolism indicate an evolutionary reliance on, and compatibility with, substantial meat intake. The implications of a modern disconnect from evolutionary dietary patterns may contribute to today’s burden of disease, increasing the risk for both nutrient deficiencies and chronic diseases.

They say that meat supplies high-quality protein and various nutrients, some of which are not always easily obtained with meat-free diets and are often already suboptimal or deficient in global populations. Removal of meat comes with implications for a broad spectrum of nutrients that need to be accounted for, whereas compensatory dietary strategies must factor in physiological and practical constraints.

Although meat makes up a small part (<10%) of global food mass and energy, it delivers most of the global vitamin B12 intake and plays a substantial role in the supply of other B vitamins, retinol, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, several minerals in bioavailable forms (e.g., iron and zinc), and a variety of bioactive compounds with health-improving potential (e.g., taurine, creatine, and carnosine).

As a food matrix, meat is more than the sum of its individual nutrients. Moreover, within the diet matrix, it can serve as a keystone food in food-based dietary interventions to improve nutritional status, especially in regions that rely heavily on cereal staples.

Finally, they say that efforts to lower global meat intake for environmental or other reasons beyond a critical threshold may hinder progress towards reducing under-nutrition and the effects this has on both physical and cognitive outcomes, and thereby stifle economic development. This is particularly a concern for populations with increased needs and in regions where current meat intake levels are low, which is not only pertinent for the Global South but also of relevance in high-income countries.

The full paper can be found here, and is part of an Animal Frontiers focus on the societal role of meat.