Extracts from an article by Eden Flaherty, first published in Landscape News and licenced under Creative Commons.

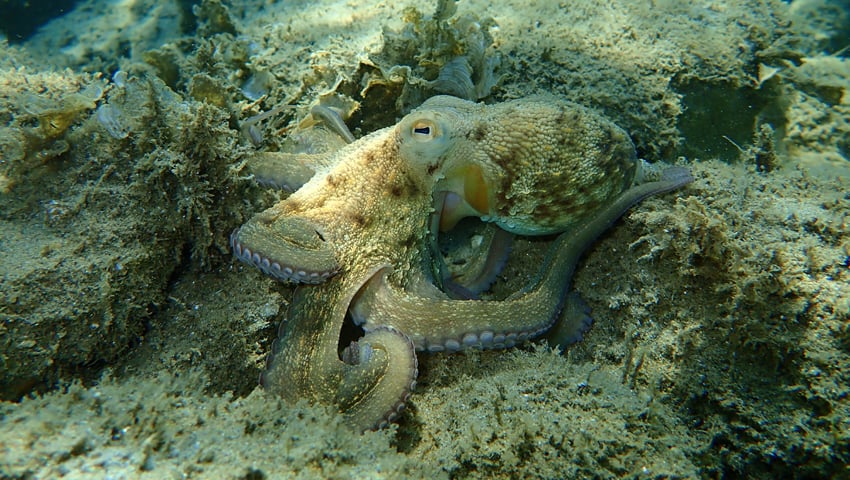

OCTOPUS farming is on the verge of a major breakthrough, with plans now well underway for the world’s first commercial octopus farm in Spain. This development has sparked fierce debate over whether these intelligent creatures should be raised for food.

While advocates say the farms could relieve pressure on wild stocks, scientists and animal rights groups have argued that it is both ethically and environmentally unsound. More generally, it highlights some of the problems of farming carnivorous seafood amid growing calls for more sustainable food.

Octopus has been eaten across Asia, the Mediterranean and South America for centuries, but annual global demand more than doubled between 1980 and 2019, driven in part by new markets like the U.S. Unlike other popular seafood, all octopus is wild-caught, whether straight to plate or via offshore floating sea cages where juveniles are raised on by-catch.

As demand has grown, so too have prices, but catches have fallen in traditional octopus fishing grounds due to decades of commercial fishing, as well as pressures such as acidification and warming waters.

Those factors have fuelled a race for octopus farming, which culminated in 2019 when the Spanish company Nueva Pescanova announced that they had successfully closed “the octopus reproduction cycle in aquaculture” – in other words, they had raised octopuses through every stage of their life cycle.

Advocates of these farms have argued that octopus farming could offer relief to wild octopus populations. But a 2019 study found that aquaculture doesn’t substantially replace caught fish. Instead, it supplements them. “Our fundamental question with this study was: does fish farming conserve wild fish?” said lead author Stefano Longo at the time. “The answer is: not really.” As Longo went on to explain, his team discovered that expanding aquaculture could in fact “contribute to greater demand for seafood as a result of the social processes that shape production and consumption.” Instead, Longo says, “aquaculture (and fisheries) could benefit from producing species lower in the food web.”

Like many of the fish we farm, octopuses are carnivorous. As such, they require large quantities of animal-based food to survive and grow in captivity. While exact figures are still hard to come by, it has been suggested that it could take up to three kilograms of feed to produce one kilogram of farmed octopus.

Much of this feed consists of fishmeal, which is manufactured by grinding up small foraging fish such as herring, anchovies and sardines, as well as by-catch and by-products of the fishing industry.

While proponents argue that this utilizes waste, research has found that around a quarter of the world’s commercially caught fish are directed straight to fishmeal production – even though 90% of it is “food grade,” meaning it can be eaten directly by people.

“In general, diverting food that can be eaten by humans to feed animals that subsequently are food for humans is not a good idea,” says Paul van Zwieten, an assistant professor of aquaculture and fisheries at Wageningen University. “In every step of the food chain, you lose roughly 90 percent of the energy,” meaning even if farmed octopus didn’t require as much feed, “there would still be a loss in energy, nutrients and proteins that we could have utilized.”

Nueva Pescanova, who will operate the planned octopus farm in Spain, have stated that they will transition to more plant-based feed in the future. But even this could divert resources away from people, with crops such as corn, wheat and soy requiring 0.2 to 0.3 hectares of land per ton of feed.

The small pelagic fish that make up the bulk of fishmeal are considered relatively stable on a global scale, with fluctuations in specific geographies “balanced out” over the world population. But farming can exacerbate these natural fluctuations and amplify the collapse of forager fish populations, recent research has shown.

Those collapses can have serious implications, as forager fish play a vital role in ocean food webs – transferring energy from plankton to larger marine life such as bigger fish, seabirds and marine mammals. What’s more, these small fish are vital for food and livelihoods in many coastal communities.

It’s also unlikely that farmed octopus will end up on plates in the countries producing the fishmeal to support the nascent industry. Instead, these aquatic resources are often being taken from communities in the Global South to feed the appetites of the Global North.

It remains to be seen how octopus farming will impact demand for fishmeal and the communities that produce it. But without even touching on the significant ethical and environmental issues surrounding octopus farming, there are clearly many social considerations to weigh up, too.

Read the original article by Eden Flaherty on Landscape News