Global forest loss surged to record highs in 2024, driven by a catastrophic rise in fires, according to new data from the University of Maryland’s GLAD Lab, made available on World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch platform.

Loss of tropical primary forests alone reached 6.7 million hectares – nearly twice as much as in 2023 and an area nearly the size of Panama, at the rate of 18 soccer fields every minute.

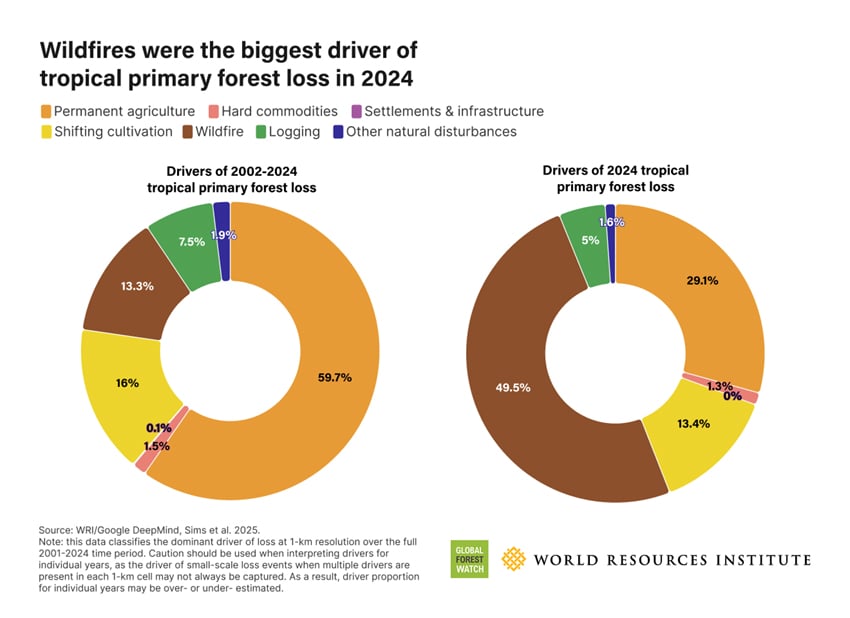

For the first time on our record, fires – not agriculture – were the leading cause of tropical primary forest loss, accounting for nearly 50 per cent of all destruction. This marks a dramatic shift from recent years, when fires averaged just 20 per cent. Meanwhile, tropical primary forest loss driven by other causes also jumped by 14 per cent, the sharpest increase since 2016.

Despite some positive developments, particularly in Southeast Asia, the overall trend is heading in a troubling direction. Leaders of over 140 countries signed the Glasgow Leaders Declaration in 2021, promising to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030. But we are alarmingly off track to meet this commitment. Of the 20 countries with the largest area of primary forest, 17 have higher primary forest loss today than when the agreement was signed.

The consequences of forest loss in 2024 have been devastating for both people and the planet. Globally, the fires emitted 4.1 gigatons of greenhouse gas emissions – releasing more than four times the emissions from all air travel in 2023. The fires worsened air quality, strained water supplies and threatened the lives and livelihoods of millions.

Elizabeth Goldman, Co-Director, WRI’s Global Forest Watch said, “This level of forest loss is unlike anything we’ve seen in over 20 years of data. It’s a global red alert – a collective call to action for every country, every business and every person who cares about a livable planet. Our economies, our communities, our health — none of it can survive without forests.”

While fires are natural in some ecosystems, those in tropical forests are mostly human-caused, often set on agricultural land or to prepare new areas for farming. In 2024, the hottest year on record, extreme conditions fuelled by climate change and El Niño made these fires more intense and harder to control. Although forests have the ability to recover from fire, the combined pressures of land conversion and a changing climate can hinder that recovery and raise the likelihood of future fires.

Top countries for forest loss

Brazil – the country with the largest area of tropical forest, accounted for 42 per cent of all tropical primary forest loss in 2024. Fires, fueled by the worst drought on record, caused 66 per cent of that loss – an over sixfold increase from 2023. Primary forest loss from other causes also rose by 13 per cent, mostly due to large-scale farming for soy and cattle, though still lower than the peaks seen in the early 2000s and in the Bolsonaro era. The Amazon experienced its highest tree cover loss since 2016, while the Pantanal suffered the highest percentage of tree cover loss in the country.

Mariana Oliveira, Director Forests and Land Use Program, WRI Brasil, said, “Brazil has made progress under President Lula – but the threat to forests remains. Without sustained investment in community fire prevention, stronger state-level enforcement and a focus on sustainable land use, hard-won gains risk being undone. As Brazil prepares to host COP30, it has a powerful opportunity to put forest protection front and center on the global stage.”

Bolivia – The country’s primary forest loss skyrocketed by 200 per cent in 2024, totaling 1.5 million hectares (3.7 million acres). For the first time, it ranked second for tropical primary forest loss only to Brazil, overtaking the Democratic Republic of Congo despite having less than half its forest area. More than half the loss was due to fires, often set to clear land for soy, cattle, and sugarcane, which turned into megafires due to heavy drought. Government policies promoting agricultural expansion worsened the problem.

Stasiek Czaplicki Cabezas, Bolivian researcher and Data Journalist for Revista Nomadas, said, “The fires that tore through Bolivia in 2024 left deep scars – not only on the land, but on the people who depend on it. The damage could take centuries to undo. Across the tropics, we need stronger fire response systems and a shift away from policies that encourage dangerous land clearing, or this pattern of destruction will only get worse.”

Colombia – Here primary forest loss increased by nearly 50 per cent. However, unlike elsewhere in Latin America, fires were not the primary cause. Instead, non-fire-related loss rose by 53 per cent, owing to instability from the breakdown in peace talks, including illegal mining and coca production.

Joaquin Carrizosa, Senior Advisor, WRI Colombia, said, “In 2023, Colombia saw the biggest drop in primary forest loss in 20 years, proving that when government and communities work together, real change is possible. The rise in primary forest loss in 2024 is a setback, but it shouldn’t discourage us as a country. We need to keep supporting local, nature-based economies – especially in remote areas – and invest in solutions that protect the environment, create jobs and foster peace.”

Democratic Republic of Congo – The DRC and the Republic of Congo (ROC) saw the highest levels of primary forest loss on record. In the ROC, primary forest loss surged by 150 per cent compared to the previous year, with fires causing 45 per cent of the damage, worsened by unusually hot and dry conditions. Like the Amazon, the Congo Basin plays a crucial role as a carbon sink, but the rising fires and forest loss now threaten its vital function. In the DRC, poverty, reliance on forests for food and energy and ongoing conflict driven by rebel groups have fueled instability and led to increased land clearing, further driving forest loss.

Teodyl Nkuintchua, Congo Basin Strategy & Engagement Lead, WRI Africa, said, “The high rates of forest loss in the DRC reflect the tough realities our communities are facing – poverty, conflict and a deep reliance on forests for survival. There’s no silver bullet, but we won’t change the current trajectory until people across the Congo Basin are fully empowered to lead conservation efforts that also support their rural economies.”

The rise in forest loss also extended beyond the tropics. The world saw a 5 per cent increase in total tree cover loss compared to 2023, adding up to 30 million hectares – an area the size of Italy. This increase was driven in part by the intense fire seasons in Canada and Russia, marking the first time that major fires raged across both the tropics and boreal forests since GFW’s record-keeping began.

Some signs of progress

However, it’s not all bad news. In Southeast Asia, there are signs of progress. Indonesia reduced primary forest loss by 11 per cent, reversing a steady rise between 2021 and 2023. Efforts under former President Joko Widodo to restore land and curb fires helped keep fire rates low, even amid widespread droughts. Similarly, Malaysia saw a 13 per cent decline and fell out of the top 10 countries for tropical primary forest loss for the first time.

Combatting forest loss

Peter Potapov, Research Professor, University of Maryland; Co-Director, Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) Lab, said, “2024 was the worst year on record for fire-driven forest loss, breaking the record set just last year. If this trend continues, it could permanently transform critical natural areas and unleash large amounts of carbon – intensifying climate change and fueling even more extreme fires. This is a dangerous feedback loop we cannot afford to trigger further.”

To meet the global goal of halting forest loss by 2030, the world must reduce deforestation by 20 per cent every year, starting immediately. In contrast, 2024 marked an 80 per cent increase in tropical primary forest loss. To combat this loss, the world needs action on multiple fronts: stronger fire prevention, deforestation-free supply chains for commodities, better enforcement of trade regulations and increased funding for forest protection – especially Indigenous-led initiatives.

Achieving this will require political will, national strategies tailored to local realities and greater support from wealthier nations to ensure forests remain standing – and are valued more alive than lost.