A LARGE continental-scale analysis conducted by 37 European researchers has concluded that the more than 50% of Europe was defined by light woodland and open vegetation, managed and shaped by a variety of animals, including large herbivores. This finding contrasts with earlier research that indicated higher woodland cover.

The researchers applied the vegetation reconstruction method REVEALS to 96 Last Interglacial pollen records. They said that “recent pollen-based reconstructions of past land cover in the Holocene 11,700 years ago] have shown that traditional comparisons of the percentage of arboreal to non-arboreal pollen strongly underestimate the cover of grass and heathland.”

These results, they say, “have important implications for our understanding of the evolutionary ecology of Europe’s native biota as well as for restoration and rewilding efforts within this biome and across the continent.”

The research paper says, “The extent of vegetation openness in past European landscapes is widely debated. In particular, the temperate forest biome has traditionally been defined as dense, closed-canopy forest; however, some argue that large herbivores maintained greater openness or even wood-pasture conditions.

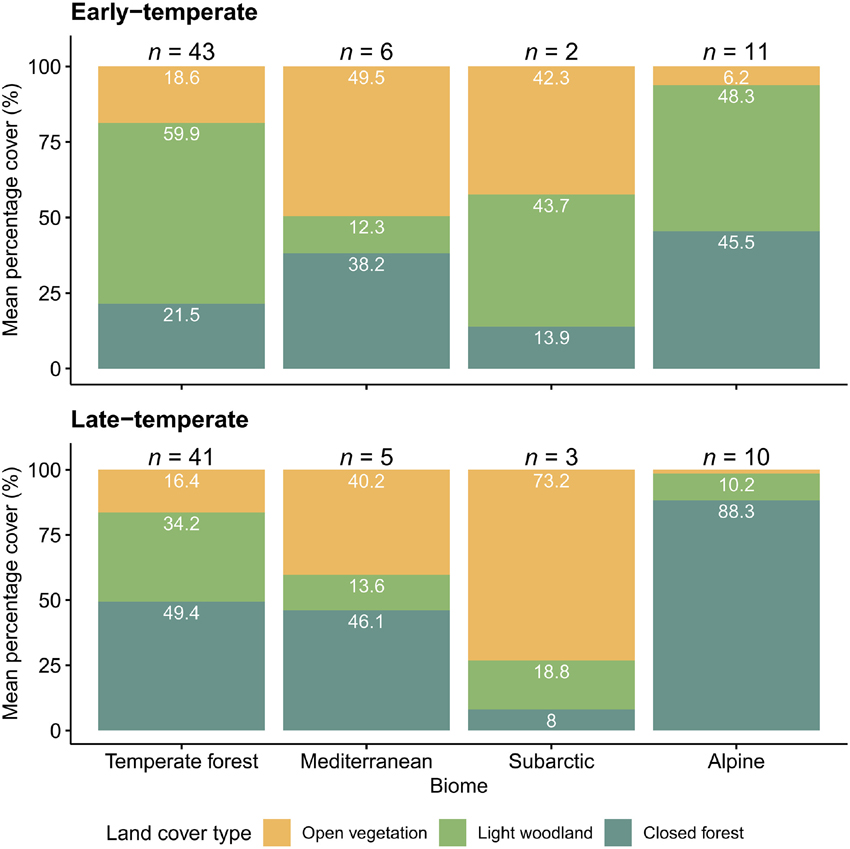

“Here, we address this question for the Last Interglacial period (129,000–116,000 years ago), before Homo sapiens–linked megafauna declines and anthropogenic landscape transformation. We applied the vegetation reconstruction method REVEALS to 96 Last Interglacial pollen records.

“We found that light woodland and open vegetation represented, on average, more than 50% cover during this period. The degree of openness was highly variable and only partially linked to climatic factors, indicating the importance of natural disturbance regimes. Our results show that the temperate forest biome was historically heterogeneous rather than uniformly dense, which is consistent with the dependency of much of contemporary European biodiversity on open vegetation and light woodland.”

This illustration, by Brennan Stokkermans, shows typical Last Interglacial fauna, such as the extinct straight-tusked elephant, an extinct rhinoceros, and aurochs, the extinct wild form of contemporary domestic and feral cattle, alongside common current species such as fallow deer, great spotted woodpecker, European robin and greylag geese. The top images show the early-temperate period, while the lower images show the late-temperate period.

The researchers say, “Our continental-scale analysis supports a growing body of local-level, proxy-based work. The presence of grasslands, meadows, and other open vegetation have been indicated by plant macrofossil, mollusc, and beetle records, large herbivore diet analyses and the presence of forb taxa that characterise grasslands.

“Such findings have provided useful indications of open vegetation during the Last Interglacial period but have previously conflicted with findings from pollen records.

“For example, in the British Isles, Coleoptera assemblages indicated the presence of up to 55% wood-pasture landscapes as well as open and closed habitats in the Last Interglacial period.

“Our results present an important step toward resolving the contradictions between the floral- and faunal-based estimations of vegetation structure during the Last Interglacial period.”