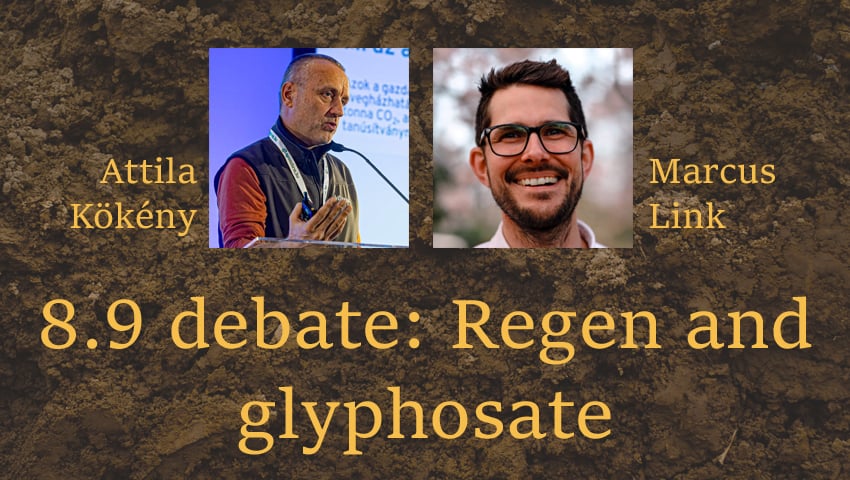

Throughout this week, two reg ag practitioner-experts have debated the contentious issue of glyphosate in a series of articles. Today we publish their closing statements

Is glyphosate critical to regenerative agriculture?

- Today Marcus Link from New Foundation Farms responds to Hungarian regenerative agriculture consultant, Attila Kökény.

- Read previous statements and responses below, starting from the bottom up.

- The views of the correspondents do not necessarily reflect the views of the 8point9.com team.

CLOSING STATEMENT BY ATTILA KÖKÉNY:

The fact that every single reader has access to unlimited amounts of food every day is thanks to the millions of unknown farmers who produce it for us, against all odds and without any financial support.

Visions are important, but customers expect a farmer to provide affordable and healthy food until a new framework is viable.

I always refer to context as the first principle of regenerative agriculture.

I think the fundamental difference between our models is that Marcus thinks in terms of feeding a narrow segment of a rich society that buys food at high prices, where there is no need for herbicides in perennial crops and livestock-based systems. Marcus has experience is with Riverford – but I am far removed from ideological, bare-ground vegetable growing as a technology that is primarily responsible for soil degradation. No chemical in the world can do as much damage to soil life and biodiversity as ploughing and tillage.

Incidentally, in my country people have low incomes and cannot afford organic prices – 90% of Hungarian organic produce is exported to rich markets. Who then feeds the poor?

For me, regenerative agriculture also means perennial crops and livestock, but that is the end phase of food system transformation and we just began this long journey.

However, 90% of the plant calories consumed globally come from annual crops, most of which are produced using soil-degrading technologies.

My job is to transform this degenerative staple food production system into a regenerative one meanwhile integrates more animals into the system, and glyphosate is essential to that.

I love the concept of radical change of Marcus, but farmers don’t have time to dream about a new system for years, they have to provide food for their customers every day and changing current practices is a huge responsibility and risk. I help broadacre farmers to transform traditional farming techniques based on ploughing to regenerative agriculture based on no-till, wide rotations, cover crops, mulching and integrated livestock management. That’s why my work is 100% practical and very careful to implement popular ideas.

In practice, it is the perennial grasses and herbs that reproduce and spread their seeds in the rows of the proposed agroforestry system that can cause significant weed pressure and yield loss in annual row crops – which can be controlled with glyphosate without tillage. In agroforestry systems, tree shading and evapotranspiration also cause significant yield depression, which, for example, according to measurements by INRAE, the largest expert on agroforestry systems, causes total yield loss below 600 mm of annual rainfall, i.e. nothing is harvested by the farmer. And we produce with less than 600mm a year and want to harvest to put bread on your table.

Mulching is an essential part of regenerative agriculture, but it is far from a foolproof solution. It reduces weed pressure, but does not eliminate weed evolution and accumulation in the field, and provides an excellent home for snails, which can kill all germinating crops overnight in a sunflower field, for example, in a rainy year.

Gaia is always looking for more biodiversity, she does not tolerate an empty soil surface, as soon as a little bare soil appears, new life will germinate there. And if you grow wheat, you want to harvest wheat, not creeping thistle. But into the small spaces between the wheat plants, Gaia sends the plants that fill every millimetre. Weed seeds arrive with the wind, bird droppings, contaminated machinery or even a muddy shoe, like the white man’s footprints on the shoes of settlers coming from Europe to North America.

Invasive weeds are a growing problem for food supplies based on annual crops, even though these plants provide 90% of the plant calories consumed by humans.

What we don’t know is whether Marcus’ system is the answer to growing these annual crops without tillage and in an environmentally friendly way.

In my system we use all the elements Marcus mentions – but growing annuals profitable is not possible without physical or chemical weed control. This is why we see bare ground in every organic farm – but bare soil surface is a clear sign of an ecological desert.

And we choose to protect the soil by controlling weeds with 2-3 drops per square metre of a quickly degrading molecule once a year, rather than mechanical weeding, which is totally destructive to soil life.

The controversy about the harmful effects of glyphosate is the result of a highly controlled fear-mongering campaign by a narrow economic lobby.

I invite everyone to see for themselves the excellent above and below ground biodiversity on a regenerative farm, the wonderful soil life, the increasing carbon in the more fertile soil, helped by the introduction of no-till technology and the use of glyphosate, which doesn’t make any harm in practice.

A farmer can be glyphosate-free if he or she has switched to selling animal products and food from mainly perennial crops, with a small amount of cereals. Under such a system, glyphosate-free is feasible, even now.

However, the current system is a long way from this, because the market does not pay for animal products, and there are increasing calls to end animal farming and a disappearing workforce in agriculture makes the work even harder.

Year after year more and more farms are going out of business due to inexorably declining profitability, while more and more annual plant-based crops are needed by customers.

The future belongs to regenerative agriculture, which if it is not achieved, there will be no future.

CLOSING STATEMENT BY MARCUS LINK (Friday 29th Sept):

The use of glyphosate is a divisive issue that goes to the heart of the future of food and farming. I appreciate that the regenerative movement is a broad church with diverse perspectives. Diversity is essential, not just in the ecosystem but in the world of ideas. I am encouraged more than ever to see it as my role to demonstrate with my colleagues at New Foundation Farms, at scale, that we can work with ecological approaches alone. To me, this is imperative not least given the latest update from the Stockholm Resilience Centre which shows that we have now crossed six planetary boundaries including novel entities and freshwater: toxins continue to be underrated in their compound effects on the ecology.

In closing, I want to get to answering some of the questions (however unsatisfactory) which I left unanswered when using the limited word count to illustrate my line of thinking.

My first serious experience inside the food supply chain was when I worked for what is now called Riverford Organic Farmers which has become the UK’s largest organic farming and direct-to-customer business. It grows and delivers a wide variety of fruit, vegetables, dairy, meat, and other groceries direct to customers’ doorsteps across the UK. The business was built out of small farms from the recognition that the supermarket model was not working for farmers or customers and out of direct experience of how harmful chemicals in conventional farming could be even when they were regarded as safe.

I joined the farm shop side of the family businesses and developed the meat operations out of the shop’s butchery, working with smaller and larger farmers, building a custom-built processing facility, growing the team, and developing the custom software which ran this side of the business for more than 10 years.

What I learnt there nearly 20 years ago was that there is a significant number of people in the UK who don’t regard themselves as faceless consumers but who recognise that they are citizens with the agency to consciously make choices about how their purchases impact ecology, society, their health, and the farmer’s wellbeing. One customer said to me when I delivered to her as part of my market research then that she considered this “eativism”: activism for a different kind of world through the food choices she made.

Today, the baseline of my approach continues to be organic, but as a research-driven serial entrepreneur, I have come into my own and explored with my colleagues at New Foundation Farms such opportunities which come about at the interface of soil science, ecology, technology, and digital platform-enabled organisational structures. They amount to nothing less than a radical supply chain disruption.

This is also entirely appropriate given the challenges we are facing as humankind in terms of anthropogenic climate change, health crises, the imperative for GHG emissions reductions, changes in our water cycles which are putting enormous pressures on food production, flood and drought mitigation as well as water quality. Farming itself is of course also in crisis: it is financially marginal, it has extraordinary high levels of mental health issues, and comes with great uncertainty. And, not least, as market research increasingly shows, people actually want to be able to choose real food, at least in the UK.

I am clear that we are at an “iPhone moment” for regenerative enterprise which is what happens when we combine regenerative opportunities in the field with new and disruptive models for farm-based businesses. This is already shifting us away from a predominantly global supply chain-based approach to a predominantly place-based approach. This kind of future is incompatible with supermarkets holding the dominant position they do in the food supply chain. Of course, like in the case of renewable energy, the old paradigm will likely run alongside the new for a while.

New Foundation Farms is about pioneering that regenerative enterprise: we exist to disrupt the supply chain. Our funding has afforded us what many farmers cannot do but which is essential at this time: we have been able to do a lot of R&D, as well as business and financial modelling. We have built a team of experts from across farming, supply chains, marketing, R&D and finance and learnt from endless amounts of data but more importantly from pioneers around the world such as Gabe Brown, Richard Perkins, and Will Harris (all entirely glyphosate free) that is possible to build complex farming businesses that sell direct-to-customer with high levels of financial, social and ecological impact.

Statistics from the UK’s government department for agriculture (DEFRA) for 2018 show that the average large, mixed, owner-occupied farm on approximately 800 acres then employed 3-4 full-time equivalents (FTEs). The farms’ marginal profits would have come from subsidies and activities other than farming. The average farmer would have been a man in his 50s.

In 2024, New Foundation Farms will begin operations on its first 250 acres. We will go on to manage, directly, six regenerative hubs across the UK with a total of 60,000 acres under management. Each hub will grow, process and deliver direct to the doorstep. We call this “hyperabundant, hyperlocal, everywhere”. Even on the first site of 250 acres, we will be employing more than 40 FTEs within the first four years who will be ecological knowledge-workers (not operatives), and who will become co-owners of the business.

For every 1,000 acres, our regenerative enterprise modelling suggests that we will be employing more than 120 well-paid FTEs from diverse backgrounds and ages in meaningful jobs across the field-to-fork operations on our rural sites. That is a multiple of 20 compared to the government statistics for comparable farms, a meaningful statistic even before all other aspects of economic, social and ecological regeneration.

This is possible when we explore opportunities beyond the broken system and within planetary boundaries.

MARCUS RESPONDS TO ATTILA (Thursday 28th Sept):

We both agree on the importance of Holistic Management (HM) which to me is about a lot more than the management of grazing operations.

Savory’s recognition was that all human affairs including wealth management depend on the photosynthetic process which makes HM an “interaction-outcomes-improvement” research framework. “Plan, monitor, control and re-plan” is its mantra. It is born out of the recognition that we can continuously develop our living knowledge of the ways in which we are in relationship with what is in our stewardship. This is why Savory lobbies for HM to be used as a tool for policy making. Policy is, after all, one way in which ideas end up shaping human actions and create different kinds of futures.

Probably the single most important device in the HM toolbox is the root cause analysis. When we have a symptom such as “perennial weeds” which interfere with our crop, the root cause analysis allows us to move from managing symptoms with glyphosate to remedying causes by building a stacked enterprise out of our understanding of how the weed works.

I don’t have enough information to assess your specific context properly, and of course context is everything. Yet, I believe it serves to illustrate the principle if I make a few assumptions.

The kind of weeds you have described on your arable land are usually found in woodland clearings. Woodland soils are similar in pH level to what is ideal for cereals in arable soils, and both soils for different reasons are nutrient rich. Yet, the cereals and deadly nightshades each prefer different fungi-microbe ratios: cereals prefer higher bacterial levels, deadly nightshades more fungi.

Here, we might be approaching the root cause: fungal development in the soil would have been interrupted regularly when the arable soils were tilled. However, with the change to the no-till regime the fungi are now able to thrive in the presence of the nutrients. They are kickstarting the process of regeneration by creating conditions favourable to the nightshades, the seeds of which are spread by wildlife.

In this way, the weeds can be regarded as ecosystem health indicators because they can tell us what is going on; they help us read the patterns of the ecosystem. Any species expresses itself when the conditions are right; their lifecycle then impacts and changes the conditions which creates a succession dynamic as other species follow. In ecology, this is called community dynamics and it is one way in which we can holistically inform our decision-making.

High nutrient levels and little organic matter in the soil means that we likely have a low carbon-nitrogen ratio. This favours the fungi as the microbes have no carbon to feed on. As nightshades prefer fungi and arable crops prefer higher microbial levels, we would want to get the carbon levels up, ideally in a truly regenerative way following the principle of feeding not the plant but the soil (which then feeds the plant). At a basic level, we could consider mulches and develop rotations of cover crops, but we could also introduce agroforestry to create arable lanes and grow pasture which we graze with livestock – not least for the source of potent living fertiliser laced with microbes. The livestock also serves as a transition tool between the pasture and the arable crop.

Gradually, a complex ecology emerges which stacks integrated layers of biodiversity and enterprise on the same land whilst sequestering carbon and improving the water cycle.

ATTILA RESPONDS TO MARCUS (Wednesday 27th Sept):

It’s difficult to go into all the details in a short article, but perhaps it needs to be clarified what is myth and what is not? The first agricultural erosion event at the beginning of the Holocene was not a worldwide event, but Dr Jean-Philippe Jenny [https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.1908179116] has studied sediments from 632 lakes around the world, and between 4000-3000 BC every continent (except Australia) shows significant erosion in sediments, coinciding with the disappearance of tree pollen. In other words, deforestation was already widespread then, due to the spread of agriculture, even though the Earth’s population is estimated to have been less than 10 million.

Today, 8 billion people wait every day for access to affordable food – but at least 828 million still do not have it.

The primary goal of agriculture has always been self-sufficiency, feeding the community, creating food security, with a single ideology: survival. For a long time, production was carried out in small family farms, as it is today in the Global South – i.e. many people are equally poor, and although the vast majority of people worked in agriculture, famine was a regular event.

The industrial revolution led to the intensification of agriculture, with more and more pristine ecosystems being destroyed to feed the growing urban population, as in the case of Leontino Balbo Jr’s 50,000ha [https://www.globalacademy.media/leontino-balbo-listening-to-nature-sustainablizes-big-agriculture-transcript/] organic sugar operation, where until relatively recently the pristine wooded savannah of the Cerrado was home to 160,000 species [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305736497904698] of plants, animals and fungi.

The farm now grows a single perennial crop in a monoculture for 6-7 years, with a competitive ability that supresses almost all other crops – this is the reason it is easily grown without herbicides. In such dense vegetation, it is not surprising that the survivors of a diverse ecosystem (that has been destroyed to grow sugar cane) find a habitat, but for me this is not a positive result, but rather disappointing. In what you call the “imperial” model, at least 20 different crops are grown over these years, with cover crops of 5-10 species complementing the main and successive secondary crops, providing grazing for animals and attracting a wealth of insects and birds. [Editor’s note: You can hear directly from Leontino Balbo Jnr here.] https://8point9.com/farm-gate-regen-rock-star-2/

In sectors based on perennial crops, such as grazing, orchards, vineyards and sugar cane plantations, the widespread availability of direct seeding machines means that herbicides are easily avoided and the soil is not tilled. Mulching instead of burning increases fertility, but as soon as you leave the world of perennials, weeds became a nuisance.

And 90% of the world’s calorie intake is based on annual staple crops, which suffer significant yield losses without weed control.

I understand that you don’t think weeds are a problem, but I have yet to meet a customer who wanted to buy creeping thistle instead of bread.

The basis of my argument is always practical: a farmer is only viable if he can make a profit. From that profit he can develop, pay rent, buy new animals, send his children to school, pay taxes and loans. If a farmer cannot make a profit, he will quickly lose his farm. Over the last 13 years we have lost 30% of the farmers.

This is true everywhere, from the half-acre rice farmer in Sri Lanka to the vast sugar cane growers, who need reliable, efficient technology to support themselves and their customers.

We know how the “imperial” regenerative model provides livelihoods and I can provide detailed evidence that the regenerative technology I use provides financial security for the farmer and excellent food quality and quantity for the customer. From a 600 hectare farm I can feed 19,000 people a year with high quality wheat alone, plus four other crops to feed at least the same number of people. If I were to switch to certified organic, that number would be reduced by around 20-40%, while destroying the soil with tillage.

So my question is: how does ecosystem management and deep regeneration provide livelihoods and food security for the population? Ideas are nice, but they can only be widely adopted if they are able to provide livelihood for the farmer. Can you tell me exactly how much food your farm produced on how many hectares, how many people it fed and how much profit it made?

Without knowing this, it is difficult to judge the viability of a deep regeneration model.

MARCUS LINK RESPONDS TO ATTILA (Tuesday 26th Sept):

There is the myth that the agricultural revolution was a uniform thing that happened to all humans everywhere about 12,000 years ago. It persists in spite of the evidence in favour of a plurality of humankinds which did different things in different places and by and large produced two kinds of design approaches: the imperial and the custodial.

The imperial approach separates humankind from nature, divides the world into resources, and views these and the land as commodities. It tends to regard evolution as a matter of competition in the face of adversity. Its economics borrow the term supply chain from the slave trade to organise extractive activity on the assumption that such chains mean greater economic benefit which can then be geared towards greater efficiency and competitive advantage.

This shows in its approach to agriculture in the simplification of formerly complex landscapes in favour of monocultures at enormous scale, which are, of course, the opposite of ecosystems.

It is possible to farm in ways that builds ecosystems. This is sometimes referred to as regenerative agriculture. Whilst regeneration is an outcome, the term is often misused to label practices. Given the low baseline of soils degenerated by decades of mechanical and chemical abuse, such practices are likely to show signs of improvement when the regime is even only slightly altered.

No-till reduces the impact on the soil and allows it to rest, and because of the rest, life returns if there is enough water for the latent biology. This is when we find ourselves faced with an abundance of ‘weeds’. Enter the weedkiller glyphosate, an apparently simple solution which promises to deliver croppable monocultures for humans and regeneration for soils.

This is, however, a flawed systems design approach. There are no weeds. There are only ecosystem health indicators that act like a mirror to our worldview and its practices. No-till may be a good if misguided start, but glyphosate is where it then already ends. We need to collaborate with biodiversity above and below ground. The enemy is not the weed but our design approach.

The custodial design approach understands humankind as of nature, as one species in the interdependent larger-than-human community. It understands land and ecosystem processes as part of this community. In this view, evolution is an outcome of collaboration and yields improve when reciprocity is greater.

The job here is to steward non-linear, complex, anti-fragile ecosystems in which food grows, abundantly. To differentiate this from the glyphosated version, I call this deep regeneration. Some say that we cannot operate agriculture at scale to feed the world with deep regeneration.

I am reassured not just by many examples from the history of humankind but also from current practitioners such as Leontino Balbo Jr. [https://8point9.com/farm-gate-regen-rock-star-2/] who has shown that we can produce organically with yields 25% higher than conventional practice at 30,000+ hectare scale when we understand our crop as part of a complex ecosystem with biodiversity levels which rival nearby national parks.

OPENING STATEMENT BY ATTILA KÖKÉNY (Monday 25th Sept):

This is a good proposition, because food production that is based on principles of regenerative agriculture can only be truly sustainable without external inputs.

In the current supply and trade structure of Western civilisation, commodities are produced on the largest land. An important activity in arable cropping is weed control, which farmers have practised for more than 12,000 years by tilling the soil.

This is about the same time as the first man-made erosion sediments appeared in lakes. Dust Bowl events were already blowing and mudflows were washing away ploughed topsoil at the beginning of Holocene, even though the ox-drawn ards tilled the soil only to the depth of current minimum tillage technology.

Think of the Greek and Spanish deserts, where rocky, barren land was once sea to sea forests and grasslands. These fertile soils have all been eroded by agriculture, which has also disrupted small water cycles, terminated local rainfalls, and turned once rich lands into man-made deserts.

Agriculture has eroded several metres of fertile topsoil all over the world and the intensification of this activity continues to cause incalculable economic, environmental and health damage.

The eradication of this Stone Age technology only began in the 1960s with the introduction of no-till farming, after the first herbicides such as 2,4D, Atrazine and Paraquat appeared. These highly toxic herbicides are dangerous to use (although, interestingly, no one is campaigning against them worldwide), so no-tillers were relieved when glyphosate entered into market. However, farming is still dominated by tillage, which is responsible for the 60-70% humus loss of our soils.

This degenerative technology can only be reversed by regenerative agriculture based on no-till. The simplest regenag is holistic grazing, as there are no more weed problems that require tilling or herbicides.

In arable farming, cover crops, crop rotation, mulching and grazing all help to reduce weed pressure, but there are no miracles.

Weeds don’t just go away, they reduce yields significantly and put our health at risk with toxic chemicals, like tropans.

Besides annual weeds, it’s the ever-growing number of perennial weeds that cause the biggest headaches.

So the farmer can choose to till the soil 5 or 6 times a year when, for example, Canada thistle appear on the fields, exhausting the plant and causing staggering structural damage, moisture loss and erosion to soil, or successfully control them with 2 to 3 drops of glyphosate per square metre in a no-till system.